the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Transport coefficients in modified Kappa distributed plasmas

Mahmood J. Jwailes

Imad A. Barghouthi

Qusay S. Atawnah

This work derives transport coefficients, i.e., electrical conductivity, thermoelectric, diffusion, and mobility coefficients, for a Lorentz plasma with a modified Kappa distribution. The derivation begins by formulating transport equations (continuity, momentum, and energy) within the five-moment approximation, using the modified Kappa distribution as the zeroth-order function. Subsequently, the corresponding momentum and energy collision terms are evaluated via the Boltzmann collision integral for different types of collisions, including Coulomb collisions, hard-sphere interactions, and Maxwell molecule collisions. Next, we use the momentum equation from the five-moment approximation to obtain the generalized Ohm’s law and extended Fick's law, leading to the transport coefficients. Furthermore, the influence of the kappa parameter on the collision terms and transport coefficients is analyzed. The traditional results based on the Maxwellian distribution are recovered in the limit as kappa parameter approaches infinity.

- Article

(3137 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

In space plasmas, the particles' velocity distribution often deviates from the Maxwellian form. These deviations arise from processes such as wave-particle interactions, turbulence, and particle acceleration at shocks, which generate non-Maxwellian distributions. Some of these distributions exhibit non-thermal suprathermal tails that follow a power-law dependence on velocity. Such distributions are well fitted by the Kappa velocity distribution (Marsch, 2006). The Kappa distribution provides a more accurate representation of the particles' velocity distribution in non-equilibrium systems compared to the Maxwellian distribution that predicts a Gaussian function behavior of the particle velocities and fails to account for the suprathermal particles. In contrast, the Kappa distribution introduces a power-law tail that decays more slowly than the exponential tail of the Maxwellian, enabling it to accurately describe systems with significant populations of high-energy particles (Vasyliunas, 1968). This flexibility is controlled by the kappa parameter, κ, which controls the sharpness of the tail. As κ increases, the distribution approaches the Maxwellian, while lower values of κ emphasize the suprathermal component (Pierrard and Lazar, 2010). With κ values usually between 2 and 6, Kappa distributions have been observed across a wide range of plasma environments, with direct measurements from several satellite missions. In the solar wind, the electron velocity distribution functions typically exhibit a thermal core, a suprathermal halo population present in all directions, and a component aligned with the interplanetary magnetic field (Pierrard et al., 2001). Kappa-distributed electrons and ions have been observed by missions such as Ulysses and Cluster. For instance, Maksimovic et al. (1997) showed that Ulysses data, fitted with Kappa functions, revealed an inverse relationship between solar wind speed and the kappa parameter κ, suggesting that suprathermal electrons influence solar wind acceleration. Similarly, Qureshi et al. (2003) also used Cluster observations to fit generalized Kappa functions to the ions' velocity distribution functions. In the Earth's magnetosheath, proton energy spectra data collected using the Heos I spacecraft confirmed that they are well fitted by Kappa distribution functions, with a kappa value around 2, particularly during crossings where no upstream waves were detected (Formisano et al., 1973). Beyond Earth, Kappa distributions have been observed in different space environments, such as Jupiter, where data from the Voyager 2 spacecraft showed that particle velocities in the planet's middle and outer magnetosphere are fitted by a Kappa distribution, with moderate kappa values indicating a transition between Maxwellian and power-law tails (Collier and Hamilton, 1995).

Given the wide range of the Kappa velocity distribution function observed in situ across planetary magnetospheres and the heliosphere and its ability to account for non-equilibrium conditions and suprathermal particles (see Pierrard and Lazar, 2010; Livadiotis, 2018; Davis et al., 2023; and Shizgal, 2007 for more details), recent studies have investigated transport coefficients in nonequilibrium plasmas with the Kappa distribution function. In particular, Wang and Du (2017) and Ebne Abbasi et al. (2017) derived the diffusion coefficient – defined as the flux of particles due to a density gradient in the plasma – using Kappa statistics to account for suprathermal tails. Similarly, Wang and Du (2017) evaluated the mobility coefficient, which describes the particle flux under an applied electric field, within the Kappa framework. Furthermore, Du (2013) and Ebne Abbasi et al. (2017) analyzed the connection between mobility, electrical conductivity, and current density to provide a consistent description of charged-particle transport in nonequilibrium systems. In addition, Du (2013); Guo and Du (2019) calculated the thermoelectric coefficient, which links electric fields to temperature gradients and leads to the generation of electric voltages and currents, based on Kappa distributions. Finally, Du (2013); Guo and Du (2019) and Ebne Abbasi and Esfandyari-Kalejahi (2019) derived the thermal conductivity, which determines heat flux under a temperature gradient, using Kappa statistics to capture deviations from equilibrium behaviour. It is important to note that these studies primarily employed the modified Kappa distribution, which assumes a κ-independent temperature, that is, both the modified Kappa and Maxwellian distributions share the same thermal energy. This formulation makes the modified Kappa produces a stronger low-energy core and suprthermal tails compared to the Maxwellian distribution. In contrast, the standard Kappa distribution, originally introduced by Olbert (1968) and Vasyliunas (1968), is defined by κ-independent thermal speeds but κ-dependent temperatures, leading to higher-energy tails than the modified Kappa and reduced core populations lower than the Maxwellian. Distinguishing between these two forms is crucial, as the choice of distribution affects the derived transport coefficients and the physical interpretation of nonequilibrium plasma behavior, as shown by Husidic et al. (2021) which derived the electrical conductivity, thermoelectric coefficient, thermal conductivity, and diffusion and mobility coefficients for electron populations described by the standard Kappa distribution and then compared these results with those obtained for the modified Kappa distribution.

All the reviewed studies used simplified collision models rather than the full Boltzmann collision integral. The simplest models appear in Wang and Du (2017) and Ebne Abbasi and Esfandyari-Kalejahi (2019), which used Krook-type or BGK operators, offering computational simplicity but limited accuracy. More physically based models – such as those proposed by Du (2013) and Guo and Du (2019) – used macroscopic transport equations derived from idealized relaxation assumptions. The most advanced work, presented by Ebne Abbasi et al. (2017), used the Fokker-Planck equation to model Coulomb collisions. While this captures cumulative small-angle scattering and better represents long-range Coulomb forces, it remains an approximation of the Boltzmann collision integral. Thus, all reviewed works share the same limitation: reliance on simplified collision models. Motivated by this issue, in this paper we propose a comprehensive re-evaluation of the transport coefficients based on the modified Kappa distribution, employing the Boltzmann collision integral as our collision model and adopting a more general and consistent approach through the five-moment approximation of the transport equations.

The transport equations describe the spatial and temporal evolution of the physically significant velocity moments (density, drift velocity, temperature, pressure tensor, stress tensor, and heat flow vector) derived as a practical reduction of the Boltzmann equation from a seven-dimensional partial differential equation (time plus phase space) to a set of four-dimensional equations (time and space). However, this process leads to an infinite chain of equations. To make the system solvable, a closure condition is applied by approximating the distribution function with a zeroth-order function and assuming that deviations from it are small. Different choices of the zeroth-order function have been used for closure, with the Maxwellian velocity distribution being the most common. The transport equations based on this assumption were first derived by Tanenbaum (1967) and Burgers (1969), followed by a subsequent review by Schunk (1977). These studies also obtained the collision terms – also known as transfer integrals – using the Boltzmann collision integral approach and expressed them in terms of the Chapman–Cowling collision integrals, as given in Chapman and Cowling (1990). To better capture anisotropies and departures from equilibrium, several studies have adopted more general zeroth-order forms. In particular, the bi-Maxwellian velocity distribution function – characterized by different temperatures parallel and perpendicular to the magnetic field – has been employed in several works (Demars and Schunk, 1979; Barakat and Schunk, 1981, 1982; Hellinger and Trávníček, 2009; Jubeh and Barghouthi, 2017). Beyond the pure bi-Maxwellian form, more advanced models incorporate anisotropy alongside nonthermal tails, skewness, or partial isotropization. For example, LeBlanc and Hubert (1997); Leblanc and Hubert (1998); Leblanc et al. (2000) introduced a hybrid distribution function that blends the bi-Maxwellian structure with additional functional forms to better match measured particle velocity spectra in space plasmas.

The approach used in this study involves developing a new transport theory that takes the modified Kappa distribution as the zeroth-order function, in which we derive the five-moment approximation of the transport equations and the collision terms via the Boltzmann collision integral for different types of collisions. We then relate the five-moment momentum equation to the generalized Ohm's law and the extended Fick's law, from which the transport coefficients are obtained. The proposed methodology is implemented as follows: In Sect. 2, we begin with the theoretical formulation of the transport equations. Starting from Boltzmann's equation and the Boltzmann collision integral, we derive the five-moment approximation and the corresponding collision terms for the modified Kappa velocity distribution function, considering arbitrary drift velocity differences as well as temperature differences between the interacting plasma species. Next, we express the resulting collision terms in a hypergeometric representation and investigate the limiting cases where the kappa parameter approaches infinity. All these calculations cover three types of collisions: Coulomb collisions, hard-sphere interactions, and Maxwell molecules collisions. We then explore how the modified Kappa distribution influences the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate, providing a physical interpretation of these effects. Subsequently, we analyse the behaviour of the collision terms in the case of Coulomb collisions, focusing on how collisions affect both the momentum and the energy of the colliding particles, and how these effects differ for Maxwellian and the modified Kappa distributions. Finally, in Sect. 3, we derive the transport coefficients using the five-moment approximation and the obtained collision terms, followed by a discussion of how these coefficients are affected by the kappa parameter. We also provide a comparison between the derived formulas and other studies, focusing on the dependence on the kappa parameter.

In dealing with plasma, we describe each species in the plasma by a separate velocity distribution function , defined such that represents the number of particles of species s, which at time t have velocity between vs and vs+dvs and positions between r and r+dr. The evolution in time of the species' velocity distribution function is determined by the net effect of collisions and the flow in phase space of species under the effect of external forces. The mathematical description of this evolution is given by the Boltzmann equation (Schunk, 1977),

Here, ∇ represents the gradient in coordinate space, is the gradient in velocity space, and as denotes the particle acceleration due to external forces. In most plasma applications, the main external forces acting on the charged particles are gravitational and Lorentz forces. With allowance for these forces, the acceleration becomes

where G is the acceleration due to gravity, es and ms are the charge and mass of species s, respectively, E is the electric field, B is the magnetic field, and c is the speed of light. The term on the right-hand side of the Boltzmann equation, , represents the rate of change of the velocity distribution function fs in a given region of phase space as a result of collisions, and its form depends on the type of collision process considered. The appropriate expression in the case of binary elastic collisions between particles (collisions governed by inverse power laws, and resonant charge exchange collisions) is the Boltzmann collision integral (Schunk, 1977; Schunk and Nagy, 2009), given by

where dvt is the velocity space volume element for the target species t, gst is the magnitude of the relative velocity of the colliding particles s and t, with gst defined as

dΩ is the element of solid angle in the s particle reference frame, θ is the scattering angle, σst(gst,θ) is the differential scattering cross-section, defined as the number of particles scattered per solid angle dΩ, per unit time, divided by the incident intensity, and the primes denote quantities evaluated after the collision. The microscopic properties of a given species s can be defined and fully described by its velocity distribution function, from which, for example, the number density of particles, the zeroth-order moment, can be obtained by integrating the distribution function over the velocity space, as

and the drift velocity of species s, the first-order moment, is given by the following relation

where 〈vs〉 is the average value of vs, with the average value of ξs(vs) at any position r and time t, defined as

For higher-order moments, it is more convenient to evaluate them with respect to the drift velocity us. Accordingly, Grad (1949) introduced the random velocity, defined as

so that the physically significant velocity moments of the species distribution function – temperature Ts, pressure tensor Ps, stress tensor τs, and heat flow vector qs – can be written as

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, I is a unit dyadic, ps is the partial pressure and defined as

The starting point for deriving the transport equations is the Boltzmann equation. These equations can be obtained by multiplying the Boltzmann equation by an appropriate function of velocity and then integrating over the velocity space. In particular, multiplying Eq. (1) by the factors 1, mscs, , mscscs, and , followed by integration over the velocity space, gives the continuity, momentum, energy, pressure tensor, and heat flow equations, respectively. Together, these form the general transport equations for species s, as presented in Schunk (1977), Schunk and Nagy (2009), and Bittencourt (2004). The general transport equations do not constitute a closed system because the equation governing the moment of order l contains the moment of order l+1. That is, the continuity equation describes the evolution of the density, but it also contains the drift velocity, and similar dependencies occur in the higher order moment equations. To close the system, it is necessary to adopt an approximate expression for the velocity distribution function fs. A common mathematical technique can be used to do that, is expanding fs in a complete orthogonal series of the form (Grad, 1949; Mintzer, 1965),

where is an appropriate zeroth-order velocity distribution function, Mi represents a complete set of orthogonal polynomials, and ai are the unknown expansion coefficients. The zeroth-order distribution function and the orthogonal set of polynomials are generally chosen so that the series converges rapidly, meaning that only a few terms in the series expansion are needed to describe the distribution function. Different levels of approximation are possible, depending on the number of terms retained in the series expansion.

2.1 The five – moment approximation

The first term in the series expansion of Eq. (14) is 1, regardless of which zeroth-order distribution function is chosen (Mintzer, 1965). Therefore, assuming the species distribution function fs is represented by the first term of the expansion, we have

The approximation in Eq. (15) reduces the general system of transport equations to just the continuity, momentum, and energy equations for each species s,

where the operation Ps:∇us corresponds to the double product of the two tensors Ps and ∇us, and the operator is defined as

The set of Eqs. (16)–(18) was initially derived with no assumption about the zeroth-order function (Tanenbaum, 1967). In the present study, we adopt the drifting modified Kappa distribution (MK) as the zeroth-order function. The drifting modified Kappa distribution is commonly written in the following form (Livadiotis, 2018; Davis et al., 2023),

where the thermal velocity of species s, denoted by ws, is given by

with ms and Ts denoting the mass and the absolute temperature of species s respectively, and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The function η(κs), which depends on the kappa parameter κs, is defined as

Here, is the invariant kappa index, and κs is a shape parameter that controls the power-law tails, sometimes referred to as the spectral index, with the condition . This condition prevents the modified Kappa distribution function in Eq. (20) from collapsing (Pierrard and Lazar, 2010). If the chosen zeroth-order distribution function satisfies

as in the drifting Maxwellian distribution and the drifting modified Kappa distribution (Scherer et al., 2019), we can write Eqs. (16)–(18) as (Schunk, 1977),

These equations are known as the five-moment approximation of the transport equations because each species is characterized by five parameters: density, three components of drift velocity, and temperature. At this level of approximation, stress, heat flow, and all higher-order velocity moments are neglected, and the species' properties are expressed in terms of density, drift velocity, and temperature.

2.2 Collision terms

The terms appearing on the left-hand side of the five-moment approximation, Eqs. (24)–(26), are called the collision terms, also known as the transfer collision integral. These terms represent the moments of the Boltzmann collision integral and describe the rate of change of density, momentum, and energy due to collisions, and they are defined as follows

where the Boltzmann's collision integral, expressed in terms of the random velocities cs and ct, takes the form:

with the functions and ft depend on ( or ct). Calculating the collision terms involves solving the integrals appearing in Eqs. (27)–(29). The process begins by substituting the Boltzmann collision integral from Eq. (30) and rewriting the resulting integrals in an equivalent form that does not require the distribution functions after the collision, . We then use the momentum transfer cross-section integral, defined as

to write the collision terms as (Schunk and Nagy, 2009),

where the dot product is written as

and the reduced mass mst is expressed as

Equations (33) and (34) are expressed in terms of the momentum transfer cross-section integral , which depends explicitly on the nature of the particles' interaction; different collision models yield different functional forms for the cross-section. In the present work, we examine three distinct cases: Coulomb collisions, hard-sphere interactions, and Maxwell molecule collisions. The momentum transfer cross-section for Coulomb collisions is given by

where es and et are the charges of species s and t, respectively, ε0 is the permittivity of free space, and ln Λ is the Coulomb logarithm. For hard-sphere interactions, the momentum transfer cross-section,

is a constant (σ is the sum of the radii of the colliding particles). In the case of Maxwell molecule collisions, the momentum transfer cross-section is

where Kst denotes a proportionality constant that measures the force magnitude between particles. Now, we proceed to calculate the momentum and energy collision terms, given in Eqs. (33) and (34), for the five-moment approximation, under the assumption that the velocity distribution function of both interacting species s and t is a drifting modified Kappa distribution. The general expressions for the collision terms are summarized below, while detailed derivations for the three types of collisions are provided in Appendix A.

where the relative drift velocity Δust and relative temperature difference are defined by

and the drift-to-thermal speed ratio εst is given by

with the reduced mass mst given in Eq. (36) and the reduced temperature Tst defined by

The kappa-dependent terms and represent, respectively, the effective collision frequency and the thermal equilibration rate (or simply the thermalisation rate) for systems described by the modified Kappa distribution, and they are defined as

where νst denote the effective collision frequency rate for systems governed by the Maxwellian distribution. The factors Ψ, D, and H forms change depending on the type of collision, such as Coulomb, hard-sphere, or Maxwell molecule collisions, and can be summarized as follows:

Coulomb collisions:

The effective collision frequency for Coulomb collisions in the Maxwellian case is

where QCo is defined in Eq. (37). The functions Φ and Ψ are given by

The kappa-dependent factors D and H are defined as

Hard-sphere interactions:

The effective collision frequency for Hard-sphere in the Maxwellian case is

where QHS is defined in Eq. (38). The functions Φ and Ψ are given by

The kappa-dependent factors D and H are defined the same as in Eqs. (52) and (53).

Maxwell molecule collisions:

The effective collision frequency for Maxwell molecule collisions in the Maxwellian case is

where QMC is defined in Eq. (39). The functions Φ and Ψ are given by

The factors D and H are defined as

The collision terms can be derived for non-drifting modified Kappa distributions by setting the drift velocities of both interacting particles s and t to zero, , which gives Δust=0 and , in Eqs. (40)–(42). The same expressions are obtained when the drift velocities of species s and t are equal, i.e., us=ut.

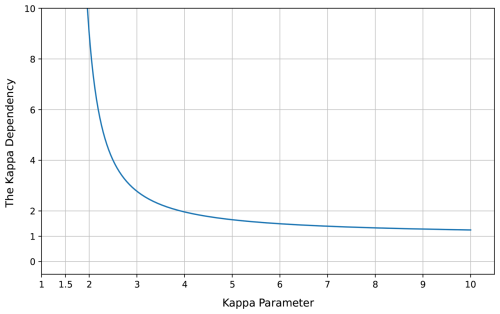

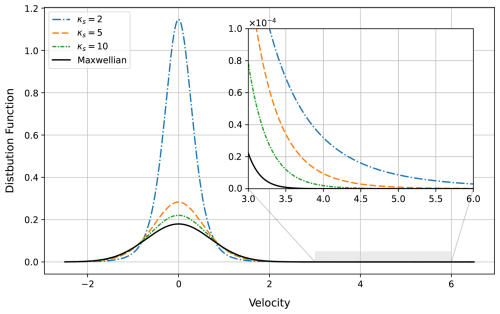

Figure 1A schematic comparison between modified Kappa velocity distributions for κs values 2, 5, and 10, and the Maxwellian velocity distribution.

2.2.1 Hypergeometric representation

The resulting collision terms in case of Coulomb collision and hard sphere interaction can be written in terms of the hypergeometric functions. This is done by expressing the Φ's and Ψ's, Eqs. (50), (51), (55), and (56), in the hypergeometric representation, such that

Coulomb collisions:

Hard-sphere interactions:

2.2.2 Limiting case: kappa parameter approaches infinity

One of the special properties of the modified Kappa distribution is that, as κs approaches infinity, the modified Kappa distribution reduces to a Maxwellian distribution (Pierrard and Lazar, 2010). Specifically, we have

and

Therefore, the modified Kappa distribution becomes identically Maxwellian distribution

as shown in Fig. 1, where as κs gets larger, the distribution becomes closer and closer to the Maxwellian distribution. This provides further confirmation that the derived formulas are correct by taking the limit of the collision terms as κ→∞, , and comparing the resulting limits with existing formulas for the Maxwellian. The collision terms given in Eqs. (40)–(42) depend on the kappa parameter through the effective collision frequency, the thermalisation rate, and the relative temperature difference, , , and , respectively. These quantities are expressed using the two functions D(κs,κt) and . Consequently, the limits of the collision terms reduce to the following limits

Hence,

With νst,T denoting the thermalisation rate for systems governed by the Maxwellian distribution, defined as

Therefore, in the limit κ approaches ∞, the collision terms (40)–(42) recover the form

The resulting limits gives exactly the same results as the Maxwellian distribution (Schunk and Nagy, 2009), with the same definitions of Φ,Ψ, and νst.

2.3 Effective collision frequency and thermalisation rate in systems with modified Kappa distributions

Within the framework of the five-moment approximation of the transport equations, the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate can be obtained directly from the momentum and energy collision terms. As derived in the previous section for the modified Kappa distribution, Eqs. (47) and (48) present the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate, which are essential for understanding the exchange of momentum and energy between particles due to collisions. The effective collision frequency reflects the average rate of how frequently collisions occur, determining the efficiency of momentum transfer within the system, while the thermalisation rate measures how rapidly the system approaches thermal equilibrium through collisions. Equations (47) and (48) show that the modified Kappa distribution affects the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate through the kappa dependent term D(κs,κt). This factor depends explicitly on the kappa parameters κs and κt of the interacting species s and t, and its form changes depending on the type of collisions under consideration. To compare the effective collision frequency and thermalisation rate of the modified Kappa and Maxwellian distributions, we must first understand how their particle velocity distributions differ. While the Maxwellian distribution has most particles concentrated around the distribution core, with low and intermediate velocity magnitudes, the modified Kappa distribution shifts this balance by increasing the number of particles both in the low-energy core and in the high-energy tails, (i.e., at low and high velocity magnitudes), as shown in Fig. 1. This redistribution in the particle velocities is directly related to the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate. In collision processes, such as Maxwell molecule collisions, where the collision frequency does not depend on particle velocity, the redistribution has no effect. The effective collision frequency and thermalisation rate remain the same even when modified Kappa distribution is used. This is confirmed by the result D=1, which shows that the kappa parameter does not change either the effective collision frequency or the thermalisation rate compared with the Maxwellian case,

In contrast, when collisions strongly depend on particle velocity, the modified Kappa distribution significantly affects both the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate. This effect becomes particularly evident in processes such as Coulomb collisions and hard-sphere interactions, where the velocity distribution strongly shapes the interaction dynamics. In these cases, the functions D vary according to the kappa parameters κs and κt, as given in Eq. (52). To compare the effective collision frequency and thermalisation rate with the Maxwellian case, and to better understand their behaviour, we consider the special case , so that the expressions, and , reduce to

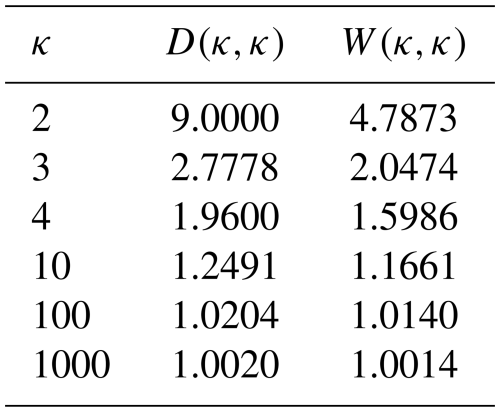

The effective collision frequency for the modified Kappa distribution in Eq. (76) agrees exactly with Livadiotis (2019) in the κ dependency, where both share the same functional form. Equations (76) and (77) show that for small values of κ, both the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate are large and decreasing as κ increases. As κ goes to infinity, the kappa term in Eq. (76) approaches 1, and the results converge to those of the Maxwellian distribution, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In this figure, we have plotted the κ dependency for both the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate; in other words, the ratios and as functions of the kappa parameter. This behaviour arises from the redistribution of the particle velocities in the modified Kappa distribution, where at low values of κ, the number of particles near the core with a small velocity magnitudes is very high compared to the Maxwellian distribution. These particles increase the collision frequency in case of Coulomb collisions and Maxwell molecules interactions, since these interactions are inversely proportional to velocity, making the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate are enhanced at low kappa values.

2.4 Variations of collision terms as a result of Coulomb collisions

The collision terms for the five-moment approximation, presented in Eqs. (40)–(42), describe how density, momentum, and energy, for particles s change under the effect of collisions. These terms depend on three variables, number density ns, drift velocity us, and temperature Ts for particles s, as well as on the parameters of particles t, number density nt, drift velocity ut, and temperature Tt. Additionally, two functions of κs and κt , D(κs,κt) and , contribute to the effective collision frequency, the thermalisation rate and the relative temperature difference. The masses of both interacting particles s and t, (ms, mt), are constant and remain unchanged throughout the collision process for all types of collisions, this makes the density coefficient to be zero according to Eq. (40). In this section, we examine how the collision terms, in the case of Coulomb collisions, vary with respect to the variables (ns, us, Ts), and the parameters (nt, ut, Tt), and we compare the results for the modified Kappa and Maxwellian distributions.

2.4.1 Maxwellian distribution

In the Maxwellian case, both functions D(κs,κt) and are set to one, see Sect. 2.2.2. Consequently, the effective collision frequency, the thermalisation rate, and the relative temperature difference in the collision terms simplify to

For clarity, we will discuss the behaviour of the collision terms in three cases, each involving a particular choice of variables or parameters.

First case, the number density of the interacting particles, ns and nt. From Eqs. (40)–(42), ns and nt appears as a product, indicating that an increase in the number density of either particle s or t will increase the influence of collisions on both the momentum and energy of the s particles. Such a result is reasonable because the number density measures particles per unit volume – more particles in the same volume lead to more collisions between s and t, causing greater changes in momentum and energy due to collisions.

Second case, the drift velocities of the interacting particles us, ut, and the temperature of the s particles Ts. Equations (40−42) show that the collision terms depend on the difference in drift velocity, , and on Ts.

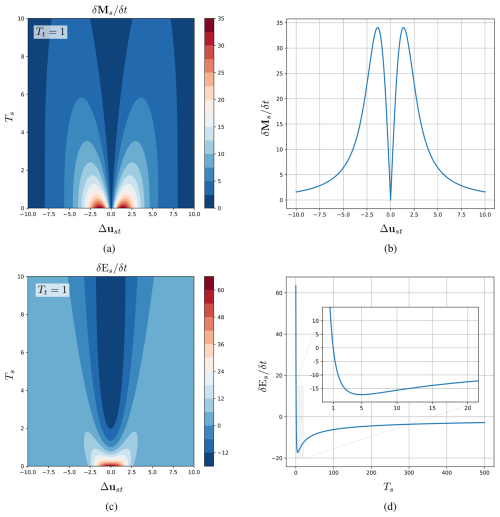

Figure 3The momentum (a) and energy (b) collision terms, respectively, for the Maxwellian velocity distribution function in the case of Coulomb collisions. (c) and (d) corresponding cross-sections to (a) and (b) at Ts=0.

Figure 3a and c display the isolines of the momentum and energy collision terms as functions of Δust and Ts, with all other constants set to 1.0 for simplicity. Assuming identical parameters for all t particles, the summation over t, in Eqs. (40)–(42), reduces to multiplication by their number, Nt, which is set to 1000 for easier comparison with other cases. Figure 3a shows the magnitude of the momentum collision term, assuming that the direction of Δust is along the z-axis. The Fig. 3a indicates that the momentum of the particles s remains unchanged when the difference in drift velocities, Δust, is zero, regardless of the temperature Ts. This means that the drift velocities of the two particles are equal or both zero, so they are not moving relative to each other, or the system has no net current flow (e.g., no applied electric field). Under these conditions, Coulomb collisions can be treated as elastic collisions, so that the total kinetic energy and momentum of the system are conserved, resulting in no change in momentum caused by the collisions. To see how the momentum collision term changes relative to Δust, we plot its cross-section at Ts=0, as shown in Fig. 3b. When one particle’s drift velocity is slightly larger than the other’s, the momentum change of particle s due to collisions increases until reaching its maximum. Beyond this maximum point, as the absolute value of the difference between the drift velocities becomes very large (i.e., us≫ut or ut≫us), collisions have less effect on the momentum. In the limit of very large Δust, the momentum collision term approaches zero because particles moving at significantly different speeds are more likely to pass each other without interacting, i.e. reducing the number of collisions. Referring back to Fig. 3a, as the temperature of the s particles increases, the impact of collisions on their momentum decreases until it eventually vanishes. This occurs because the effective collision frequency, νst, for Coulomb collisions in the Maxwellian case, defined in Eq. (49), between the particles decreases with increasing temperature as

showing that collisions become less probable at higher temperatures, leading to a reduction in their influence on momentum. Figure 3c represents the energy collision term. The graph shows that maximum energy exchange occurs when the difference in the drift velocities is zero. As mentioned earlier, in this case, both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved, meaning there is no change in these quantities.

Figure 4The momentum and energy collision terms for the Maxwellian velocity distribution function in the case of Coulomb collisions, at different values of Tt: 2, 5, and 10.

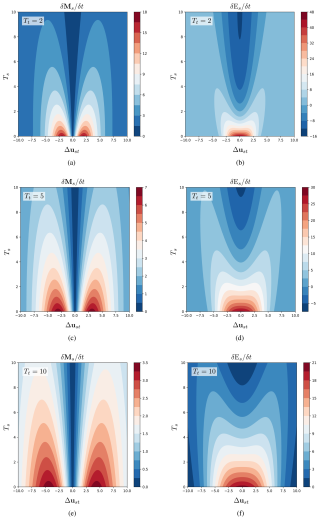

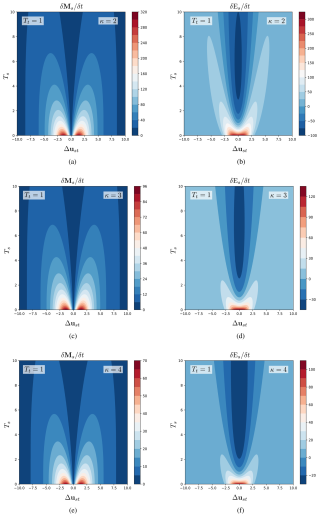

Figure 5The momentum and energy collision terms for the modified Kappa velocity distribution function in the case of Coulomb collisions at different values of κ: 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 6The cross-section of the momentum and energy collision terms for the modified Kappa and Maxwellian velocity distribution functions in the case of Coulomb collisions at Ts=0.

The change in the energy comes from the potential energy, specifically the difference between the temperatures of the interacting particles. Figure 3d shows the cross-section of the energy collision term for the case Δust=0. At Ts=0, the energy exchange between particles is most significant, as particles s gain temperature from particles t. As Ts increases and approaches Tt, the energy transfer decreases and vanishes when the temperatures of the two species are equal. This occurs at in Fig. 3d, where ΔTst=0, leading to no energy transfer and the energy collision term becomes zero. As the temperature of particles s increases above the temperature of particles t, Ts>Tt, particles s lose temperature to particles t, and the energy collision term becomes negative and decreases until it reaches a minimum value, which in our case occurs at Ts=5. Beyond this point, the increase in the temperature of particles s reduces the effective collision frequency, see Eq. (79). As a result, particles s keep their temperature without losing any of it to particles t. This explains the subsequent increase in the change of energy. Eventually, as the effective collision frequency tends to zero, no further collisions occur, and the temperature change vanishes, making the energy collision term approach zero as Ts goes to infinity. Back to Fig. 3c, as the absolute value of the difference in drift velocity increases, the distance between particles also increases. This greater distance between particles makes collisions less likely, which in turn reduces energy exchange for species s. Consequently, the energy collision term approaches zero as the drift velocity difference, Δust, tends to ±∞, similar to the behaviour of the momentum collision term when either us≫ut or ut≫us.

Third case, the temperature of the t particles Tt. In Fig. 4, we plot the isolines of the collision terms under the same conditions as in Fig. 3, but for different values of Tt. As Tt increases, the collision terms exhibit the same overall behaviour, but their magnitude decreases. For example, drops from 35 at Tt=1 (Fig. 3a) to 18 at Tt=2 (Fig. 4a), 7 at Tt=5 (Fig. 4c), and 3.5 at Tt=10 (Fig. 4e). A similar trend is observed for , which drops from 60 to 48, then to 30, and finally to 21 (Figs. 3c, 4b, d, and f). This reduction occurs because, as the temperature increases, the number of collisions decreases as mentioned before. Additionally, Fig. 4 shows that the range of Δust contributing to the collision terms (red area along the horizontal axis) expands with Tt, since fewer collisions allow particles to accelerate more under external forces, increasing their drift velocities.

2.4.2 Modified Kappa distribution

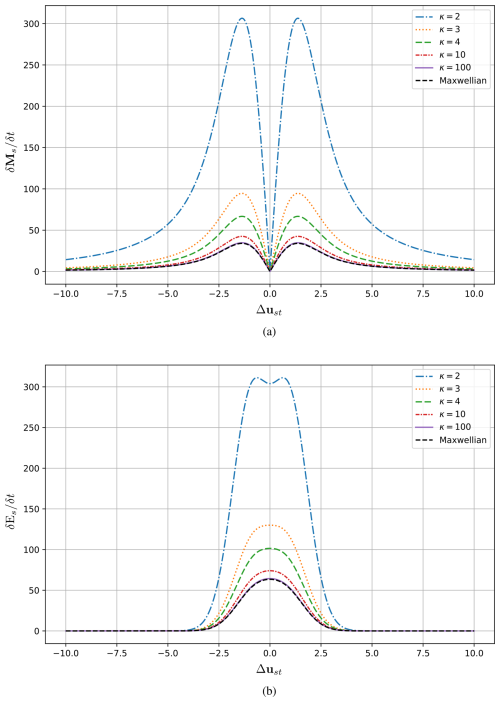

The modified Kappa distribution affects the collision terms through two functions D(κs,κt) and , which appear in the effective collision frequency, the thermalisation rate and the relative temperature difference. Assuming equal kappa values for both species, s and t, , allows for a direct comparison with the Maxwellian case. To understand how modified Kappa distribution changes the collision terms, we plot the isolines of the momentum and energy collision terms as functions of Δust and Ts, as shown in Fig. 5, with the same conditions as in Fig. 3a, for various κ values. Cross-sections at Ts=0 are shown in Fig. 6. For the momentum collision term, the behavior is similar to the Maxwellian case, with D(κ,κ) scaling the effective collision frequency, as shown in Figs. 5 and 6a. At low κ, the effective collision frequency increases, as discussed in Sect. 2.3, leading to greater momentum transfer due to collisions at these values. For the energy collision term, the function W(κ,κ), defined as

appears in the first term of Eq. (42), while D(κ,κ) contributes to the second term. The general behavior of the energy coefficient is approximately the same as in the Maxwellian case, particularly at high κ values. However, at low kappa values, particularly κ=2, , as outlined in Table 1, making the kinetic term dominant and producing peaks near zero, as shown in Fig. 6b. Overall, both collision terms decrease with increasing κ, converging toward the Maxwellian result, confirming the result of Sub-subsection 2.2.2.

In this section, we derive and discuss the behavior of the transport coefficients – namely, the electrical conductivity σe, thermoelectric coefficient αe, diffusion coefficient De, and mobility coefficient μe – for a Lorentz plasma using the modified Kappa distribution. A Lorentz plasma is a type of plasma in which the contribution of electron-electron collisions is negligible compared to electron-ion collisions. In this model, electrons are considered to move relative to nearly stationary ions because their much smaller mass allows them to move much faster (Du, 2013). The Lorentz plasma model is particularly useful for calculating transport coefficients, such as electrical conductivity, because electron-electron collisions do not contribute significantly to these properties. The transport coefficients for Lorentz plasma without a magnetic field appear in the following macroscopic laws (Husidic et al., 2021),

Equation (81) represents generalizes Ohm's law, where E denotes the electric field and Je is the current density, defined as (Schunk and Nagy, 2009),

with e being the charge, ne the electron density, and ui,ue the ion and electron velocities, respectively. Similarly, Eq. (82) extends Fick's law to account for electric field effects, with Γe denotes the particle flux density, defined as (Schunk and Nagy, 2009),

3.1 Derivation of transport coefficients

The transport coefficients can be obtained by deriving Eqs. (81) and (82) using the five-moment approximation. For a simple electron-ion collision, using Eq. (41), the momentum equation with a drifting modified Kappa distribution, can be expressed as

with the momentum collision term is given by

where is the effective collision frequency for the modified Kappa distribution, as defined in Eq. (47). In Eq. (85), the electron drift velocity is assumed negligible compared to the thermal velocity, which is equivalent to setting ϵei=0 and therefore Φ(0)=1 in Eq. (41). To obtain the transport coefficients, we adopt the standard approximations. First, we assume a steady and low-inertia regime so that . Second, we neglect external gravity and magnetic fields, i.e., G=0 and B=0, which corresponds to unmagnetized scalar transport. For convenience, we also take the background ion flow to be ui≈0. Under these assumptions, the electron momentum equation reduces to

since

To derive the electrical conductivity and the thermoelectric coefficients, we begin by setting ∇ne=0 and using the definition of the current density Je with ui≈0, we write

Substituting this expression into the electron momentum Eq. (87), we obtain

Solving the equation for the electric filed gives

By comparing this result with the generalized Ohm's law, Eq. (81), we can identify the electrical conductivity and the thermoelectric coefficient as

Similar to how we derive the electrical conductivity and the thermoelectric coefficient, the diffusion and mobility coefficients can be obtained by setting ∇Te=0 and using the definition of the particle flux density, Γe, in Eq. (84), Eq. (87) gives

By comparing this to Fick's law, Eq. (82), the diffusion and mobility coefficients are identified as

3.2 Discussion of transport coefficients

From the first look at the derived transport coefficients, we can see that they satisfy the familiar relation between the electric conductivity and the mobility coefficient

and Einstein relation

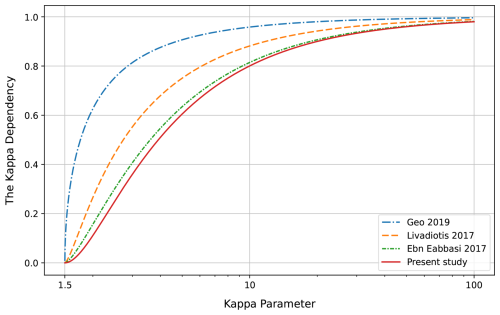

The resulting transport coefficients show a different dependency on the kappa parameters. The thermoelectric coefficient αe has no kappa term in it. On the other hand, the electrical conductivity, diffusion, and mobility coefficients all include the same kappa term, which appears through the effective collision frequency . The transport coefficients-electrical conductivity, diffusion, and mobility-are inversely proportional to the effective collision frequency. As discussed earlier, when , the effective collision frequency for the modified Kappa distribution influences different types of collisions in distinct ways. Consequently, the impact of the modified Kappa distribution on the transport coefficients depends on the specific type of collision. For Maxwell molecules, the effective collision frequency remains identical to that of the Maxwellian distribution, implying that the modified Kappa distribution does not affect the transport coefficients in this kind of collision. However, for Coulomb collisions and hard-sphere interactions, the effective collision frequency increases as κ decreases, leading to a decrease in the transport coefficients at low values of κ compared to the Maxwellian case, as shown in Fig. 7, where we have plotted the kappa dependency for the electrical conductivity as functions of the kappa parameter. As κ approaches ∞, the effective collision frequency reduces to the Maxwellian case vei, making the transport coefficients recover their Maxwellian limits. The obtained transport coefficients have both differences and similarities with other studies. One can compare this with a number of studies that predicted a similar trend in the transport coefficients. In Fig. 7, we also show the dependence on the κ parameter of the electrical conductivity from different studies and compare it with the present work, by plotting the ratio as a function of κ, where , and

All studies show a different dependence on the κ parameter, but they still exhibit the same behavior: at low values of κ, the electrical conductivity becomes smaller compared to the Maxwellian case, and as κ increases, we approach the Maxwellian case but never exceed it. This confirms that plasmas with larger κ values are better conductors. Thus, deviations from the Maxwellian limit lead to a decrease in electrical conductivity. Figure 7 also shows that, the curves converge to the present work. This can be explained through the collision models used in the derivation of the transport coefficients. In each study, a more general collision term model was used. For example, Guo and Du (2019) used the Linearized Lorentz Collision Model with a relaxation-time approximation for electron-ion collisions. Livadiotis (2017) used the Fokker–Planck collision operator with simplifications related to the direction of the electric field. Finally, the work of Ebne Abbasi et al. (2017) used the Fokker–Planck collision operator, where the derivation was generalized, and the only approximation occurred in the last step for the hypergeometric function. The work of Ebne Abbasi et al. (2017) is the closest to our present study, as can be seen clearly in the figure. The reason is that, in our study, we used the full Boltzmann collision integral, of which the Fokker–Planck operator can be considered an approximation.

For a Lorentz plasma described by a modified Kappa distribution, we have derived the transport coefficients: electrical conductivity, thermoelectric, diffusion, and mobility. The derivation begins with deriving a closed system of transport equations for isotropic plasmas within the five-moment approximation. In these equations, the transport properties of a given species are defined with respect to the random velocity of that species, where the species velocity distribution function is expanded in an orthogonal polynomial series about a drifting modified Kappa weighting function. By taking only the first term of the expansion and neglecting all higher order moments of the velocity distribution, we obtain the five-moment approximation. The corresponding momentum and energy collision terms were evaluated via the Boltzmann collision integral for several interaction types, including Coulomb collisions, hard-sphere interactions, and Maxwell molecule collisions. Given the complexity of the collision terms, the final expressions were represented using hypergeometric functions to simplify numerical calculations. Next, we investigated the limiting case in which the kappa index approaches infinity, where the collision terms reduce to Maxwellian form. Then we analyzed the influence of the kappa index on the effective collision frequency and thermalisation rate. It was observed that systems described by modified Kappa distribution exhibit distinct behaviour compared to those with Maxwellian distribution. The modified kappa distribution directly influences collision dynamics, where, for interactions in which collision frequency is velocity-independent, such as Maxwell molecule interaction, the distribution does not affect the effective collision frequency or thermalisation rate. In contrast, for velocity-dependent collisions, such as Coulomb and hard-sphere interactions, smaller κ values increase collision frequency and thermalization, and larger κ values approach the Maxwellian limit. We further examined the influence of the kappa index on the momentum and energy collision terms of the particles during Coulomb collisions. At low kappa parameter values, the number of collisions increases significantly, making both the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate produce greater changes in the momentum and energy of the particles, while larger κ values recover Maxwellian behavior.

Starting from the momentum equation and applying suitable assumptions for an unmagnetized, steady-state plasma, explicit expressions for the electrical conductivity, thermoelectric coefficient, diffusion coefficient, and mobility coefficient were obtained for the modified Kappa distribution. The analysis reveals that while the thermoelectric coefficient is unaffected by the κ parameter, the electrical conductivity, diffusion, and mobility coefficients are all inversely proportional to the effective collision frequency, thereby reflecting its κ dependency. Furthermore, the results indicate that lower κ values lead to an increase in collision frequency and consequently a decrease in the transport coefficients. In the limit (κ→∞), the coefficients naturally reduce to Maxwellian form, confirming the consistency of the approach.

While the current study provides an important step towards a comprehensive non-Maxwellian transport theory, the present work is limited in several ways. First, the approach was derived within the five-moment approximation of the transport equation, considering only the first term of the expansion and neglecting higher-order moments. This simplification represents a poor approximation, as the neglected terms could significantly affect the system’s behavior. Second, the analysis assumes isotropic plasmas, which restricts its applicability to real space plasma environments. In reality, most space plasmas are magnetized and exhibit temperature and pressure anisotropies. Ignoring these effects may overlook important physical mechanisms that govern plasma dynamics. Third, the Coulomb collision cross-section was simplified using a constant Coulomb logarithm and large-velocity approximation, which may affect quantitative accuracy at low velocities (Fichtner et al., 1996). Finally, the model employs the modified Kappa distribution, whose applicability breaks down for , as lower values cause divergent moments and thermodynamic inconsistencies. In this regime, the functions D(κ,κ) and H(κ) diverge, making the effective collision frequency and the thermalisation rate become unphysical. Therefore, the derived collision terms and transport coefficients are valid only for .

Future work should address the current model's limitations through several key extensions. First, developing a comprehensive transport theory that accounts for the modified Kappa velocity distribution, would significantly advance the framework beyond the standard Maxwellian assumption. This can be achieved by expanding the species distribution function in a generalized orthogonal polynomial series with a κ-weighting function, allowing for systematic derivation of various approximations (e.g. eight-, ten-, thirteen-, and twenty-moment models). Second, extending the theory to anisotropic plasmas – where pressure and temperature vary with direction – would enhance its realism and applicability, particularly in magnetized and space plasma environments. In addition, incorporating the exact velocity-dependent Coulomb cross-section would improve the accuracy of the collision transfer integrals. Furthermore, adopting the Regularized Kappa Distribution proposed by (Scherer et al., 2017, 2019), which preserves the core features of the κ-function while ensuring finite moments for all κ>0 and maintaining thermodynamic consistency, would provide a more stable and physically meaningful representation.

This appendix presents the derivation of the collision terms for each type of collision for the drifting modified Kappa distribution introduced in Sect. 2.2.

A1 Coulomb collisions

The collision terms for Coulomb collisions can be obtained by substituting Eq. (37) into Eqs. (32)–(34), leading to the following form

A2 The Momentum Coefficient

The momentum coefficient for Coulomb collision is given in Eq. (A2). Evaluating it requires computing the integral

to do this, we begin by rewriting the distribution function of the interacting species s and t in an integral representation, instead of writing them in the form of Eq. (20), as

Substituting the distributions given in Eqs. (A5) and (A6) in the integral, Eq. (A4), gives

To solve the integral in Eq. (A7), we introduce the following transformation

The constant A and B are defined by:

Here c∗ and g∗ are expressed as:

with

Calculating the determinant of the Jacobian matrix J for the transformation described in Eqs. (A8)–(A10) gives

Applying the transformation make the integrals in Eq. (A7) independent of each other, so by evaluating the integrals with respect to and ξ2, and rewriting the g* integral, we have

where D(κs,κt) is defined in Eq. (52).

The integral on gst can be solved by setting z-axis in the direction of vector Δust, so that the angle between gst and Δust corresponds to the polar angle in spherical coordinates. We then transform the integrals into spherical coordinates and perform the integration, to get

Substituting Eq. (A16) into Eq. (A2), we can write the momentum coefficient for Coulomb collision as

A3 The Energy Coefficient

The energy coefficient for Coulomb collisions is given in Eq. (A3). Substituting the dot product from Eq. (35) into the integral

produces three integrals, which can be evaluated by following the same steps as the integral in Eq. (A4), where we substitute the distributions given in Eqs. (A5) and (A6) into the integrals, and apply the transformation mentioned in Eqs. (A8)–(A10). This results in two integrals that depend on gst, which can be evaluated using the same steps used for the integral in Eq. (A15). Combining all integrals, we obtain:

Substituting Eq. (A19) into Eq. (A3), we can write the energy coefficient for Coulomb collision as

where and ΨCo are defined as in Eqs. (44) and (51), respectively.

A4 Hard-sphere interactions

The collision terms for hard-sphere interactions can be obtained by substituting Eq. (38) into Eqs. (32)–(34), leading to the following form

Calculating the collision terms for hard-sphere interactions follows the same steps as those applied previously for the Coulomb collision. The main difference between the integrals in Eqs. (A21)–(A23) and (A1)–(A3) is that gst has a power of 1 rather than −3. This difference affects only the final integrals. Using the same technique, we obtain the momentum coefficient for hard-sphere interactions,

and the energy coefficient for hard-sphere interactions,

A5 Maxwell molecule collisions

The collision terms for Maxwell molecule collisions can be obtained by substituting Eq. (39) into Eqs. (32)–(34), leading to the following form

There's no integration technique required to evaluate Eqs. (A26)–(A28), since after rewriting the relative velocity in Eq. (4) and the dot product in Eq. (35) in terms of the random velocities cs and ct, allows us to use the following expectation values for the modified Kappa distribution,

where A is constant and α denotes the species type s or t, to obtain the momentum coefficient for Maxwell molecule collisions

and the energy coefficient for Maxwell molecule collisions

where is defined in Eq. (57).

No external or third-party software code was used in this work beyond standard, widely available plotting functions provided by common scientific computing environments. The plotting routines applied in this study consist solely of simple function evaluations and visualizations based directly on the analytical formulas already presented in the paper. All formulas, computational steps, and expressions used to generate the figures are fully described within the paper itself. Because no custom or novel software code was developed and because the figures can be reproduced entirely from the equations provided, there is no separate software package to archive, cite, or deposit in a public repository.

This study did not generate or use any external research data. All figures are produced directly from analytical formulas included within the paper, and no numerical datasets were created, collected, or processed. As such, no datasets exist to deposit in a public repository, and no data DOI or persistent URL is applicable.

M. J. Jwailes carried out the theoretical work, derived the framework used to obtain the figures and results, wrote the initial manuscript, and led the discussion of the findings. I. A. Barghouthi proposed the research idea, supervised the study, verified the validity of the results, and assisted in scientific editing of the manuscript. Q. S. Atawnah contributed to the final revisions of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors thank the reviewers, Dr. Horst Fichtner and Prof. Marina Stepanova, for their critical reading of the manuscript and for their constructive suggestions, which significantly improved the quality of this work.

This paper was edited by Georgios Balasis and reviewed by Horst Fichtner and Marina Stepanova.

Barakat, A. R. and Schunk, R. W.: Momentum and energy exchange collision terms for interpenetrating bi-Maxwellian gases, Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 14, 421, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/14/3/013, 1981. a

Barakat, A. R. and Schunk, R. W.: Transport equations for multicomponent anisotropic space plasmas: a review, Plasma Physics, 24, 389, https://doi.org/10.1088/0032-1028/24/4/004, 1982. a

Bittencourt, J.: Fundamentals of Plasma Physics, Springer New York, 3rd ed edn., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-4030-1, 2004. a

Burgers, J.: Flow Equations For Composite Gases, Applied Mathematics And Mechanics, Academic Press, https://www.sciencedirect.com/bookseries/applied-mathematics-and-mechanics/vol/11/suppl/C?utm_source=chatgpt.com (last access: 3 December 2025), 1969. a

Chapman, S. and Cowling, T.: The Mathematical Theory of Non-uniform Gases: An Account of the Kinetic Theory of Viscosity, Thermal Conduction and Diffusion in Gases, Cambridge Mathematical Library, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521408448, 1990. a

Collier, M. R. and Hamilton, D. C.: The relationship between kappa and temperature in energetic ion spectra at Jupiter, Geophysical Research Letters, 22, 303–306, https://doi.org/10.1029/94GL02997, 1995. a

Davis, S., Avaria, G., Bora, B., Jain, J., Moreno, J., Pavez, C., and Soto, L.: Kappa distribution from particle correlations in nonequilibrium, steady-state plasmas, Physical Review E, 108, 065207, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.108.065207, 2023. a, b

Demars, H. G. and Schunk, R. W.: Transport equations for multispecies plasmas based on individual bi-Maxwellian distributions, Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 12, 1051, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/12/7/011, 1979. a

Du, J.: Transport coefficients in Lorentz plasmas with the power-law kappa-distribution, Physics of Plasmas, 20, 092901, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4820799, 2013. a, b, c, d, e

Ebne Abbasi, Z. and Esfandyari-Kalejahi, A.: Transport coefficients of a weakly ionized plasma with nonextensive particles, Physics of Plasmas, 26, 012301, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5051585, 2019. a, b

Ebne Abbasi, Z., Esfandyari-Kalejahi, A., and Khaledi, P.: The collision times and transport coefficients of a fully ionized plasma with superthermal particles, Astrophysics and Space Science, 362, 103, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10509-017-3081-4, 2017. a, b, c, d, e

Fichtner, H., Sreenivasn, S. R., and Vormbrock, N.: Transfer integrals for fully ionized gases, Journal of Plasma Physics, 55, 95–120, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022377800018699, 1996. a

Formisano, V., Moreno, G., Palmiotto, F., and Hedgecock, P. C.: Solar Wind Interaction with the Earth's Magnetic Field 1. Magnetosheath, Journal of Geophysical Research, 78, 3714–3730, https://doi.org/10.1029/JA078i019p03714, 1973. a

Grad, H.: On the kinetic theory of rarefied gases, Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, 2, 331–407, https://doi.org/10.1002/cpa.3160020403, 1949. a, b

Guo, R. and Du, J.: Transport coefficients of the fully ionized plasma with kappa-distribution and in strong magnetic field, Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 523, 156–171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2019.02.011, 2019. a, b, c, d

Hellinger, P. and Trávníček, P. M.: On Coulomb collisions in bi-Maxwellian plasmas, Physics of Plasmas, 16, 054501, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3139253, 2009. a

Husidic, E., Lazar, M., Fichtner, H., Scherer, K., and Poedts, S.: Transport coefficients enhanced by suprathermal particles in nonequilibrium heliospheric plasmas, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 654, A99, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202141760, 2021. a, b

Jubeh, W. N. and Barghouthi, I. A.: Hypergeometric function representation of transport coefficients for drifting bi-Maxwellian plasmas, Physics of Plasmas, 24, 122104, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5000937, 2017. a

LeBlanc, F. and Hubert, D.: A Generalized Model for the Proton Expansion in Astrophysical Winds. I. The Velocity Distribution Function Representation, The Astrophysical Journal, 483, 464, https://doi.org/10.1086/304232, 1997. a

Leblanc, F. and Hubert, D.: A Generalized Model for the Proton Expansion in Astrophysical Winds. II. The Associated Set of Transport Equations, The Astrophysical Journal, 501, 375, https://doi.org/10.1086/305789, 1998. a

Leblanc, F., Hubert, D., and Blelly, P.-L.: A Generalized Model for the Proton Expansion in Astrophysical Winds. III. The Collisional Transfers and Their Properties, The Astrophysical Journal, 530, 478, https://doi.org/10.1086/308335, 2000. a

Livadiotis, G.: Kappa distributions: Theory and applications in plasmas, Elsevier, https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/edited-volume/9780128046388/kappa-distributions (last access: 3 December 2025), 2017. a

Livadiotis, G.: Kappa distributions: Thermodynamic origin and Generation in space plasmas, IOP Publishing, 1100, 012017, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1100/1/012017, 2018. a, b

Livadiotis, G.: Collision frequency and mean free path for plasmas described by kappa distributions, AIP Advances, 9, 105307, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5125714, 2019. a

Maksimovic, M., Pierrard, V., and Riley, P.: Ulysses electron distributions fitted with Kappa functions, Geophysical Research Letters, 24, 1151–1154, https://doi.org/10.1029/97GL00992, 1997. a

Marsch, E.: Kinetic Physics of the Solar Corona and Solar Wind, Living Reviews in Solar Physics, 3, https://doi.org/10.12942/lrsp-2006-1, 2006. a

Mintzer, D.: Generalized Orthogonal Polynomial Solutions of the Boltzmann Equation, The Physics of Fluids, 8, 1076–1090, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1761357, 1965. a, b

Olbert, S.: Summary of Experimental Results from M.I.T. Detector on IMP-1, in: Physics of the Magnetosphere, edited by: Carovillano, R. L., McClay, J. F., and Radoski, H. R., Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 641–659, ISBN 978-94-010-3467-8, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-3467-8_23, 1968. a

Pierrard, V. and Lazar, M.: Kappa Distributions: Theory and Applications in Space Plasmas, Solar Physics, 267, 153–174, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-010-9640-2, 2010. a, b, c, d

Pierrard, V., Maksimovic, M., and Lemaire, J.: Core, Halo and Strahl Electrons in the Solar Wind, Astrophysics and Space Science, 277, 195–200, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012218600882, 2001. a

Qureshi, M. N. S., Pallocchia, G., Bruno, R., Cattaneo, M. B., Formisano, V., Reme, H., Bosqued, J. M., Dandouras, I., Sauvaud, J. A., Kistler, L. M., Möbius, E., Klecker, B., Carlson, C. W., McFadden, J. P., Parks, G. K., McCarthy, M., Korth, A., Lundin, R., Balogh, A., and Shah, H. A.: Solar Wind Particle Distribution Function Fitted via the Generalized Kappa Distribution Function: Cluster Observations, AIP Conference Proceedings, 679, 489–492, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1618641, 2003. a

Scherer, K., Fichtner, H., and Lazar, M.: Regularized κ-distributions with non-diverging moments, Europhysics Letters, 120, 50002, https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/120/50002, 2017. a

Scherer, K., Lazar, M., Husidic, E., and Fichtner, H.: Moments of the Anisotropic Regularized κ-distributions, The Astrophysical Journal, 880, 118, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab1ea1, 2019. a, b

Schunk, R. and Nagy, A.: Ionospheres: Physics, Plasma Physics, and Chemistry, Cambridge Atmospheric and Space Science Series, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511635342, 2009. a, b, c, d, e, f

Schunk, R. W.: Mathematical structure of transport equations for multispecies flows, Reviews of Geophysics, 15, 429–445, https://doi.org/10.1029/RG015i004p00429, 1977. a, b, c, d, e

Shizgal, B. D.: Suprathermal particle distributions in space physics: Kappa distributions and entropy, Astrophysics and Space Science, 312, 227–237, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10509-007-9679-1, 2007. a

Tanenbaum, B.: Plasma Physics, McGraw-Hill Physical and Quantum Electronics Series, McGraw-Hill, https://books.google.ps/books/about/Plasma_Physics.html?id=GA3TvwEACAAJ&redir_esc=y (last access: 3 December 2025), 1967. a, b

Vasyliunas, V. M.: A Survey of Low-Energy Electrons in the Evening Sector of the Magnetosphere with OGO 1 and OGO 3, Journal of Geophysical Research, 73, 2839–2884, https://doi.org/10.1029/JA073i009p02839, 1968. a, b

Wang, L. and Du, J.: The diffusion of charged particles in the weakly ionized plasma with power-law kappa-distributions, Physics of Plasmas, 24, 102305, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4996775, 2017. a, b, c